“What's the worst that could happen?”: A worked example of how we deal with live incidents.

I am the Principal DevOps Engineer for the Core Customer Tribe at Sky Betting & Gaming. One of my duties is to help mentor our DevOps Engineers and help them improve. One of the hardest aspects of that is helping them to deal with failed changes. We make a lot of live changes in Core Customer, and for the most part they go smoothly, but mistakes happen. I’d like to take you through a recent example of where just such a mistake did happen, explain why it was handled well, and why it shows that this aspect of my job is hard.

Some Background

The incident in question was caused by a config change to the JMX settings of a number of Java applications we run. We use JMX to gather metrics from these applications, and a previous attempt at this change had already caused an incident that stopped these metrics from being collected. It was not customer impacting, but it did mean this change was already fairly high stress for the Engineer performing it. A fix had been added to the change for the metrics issue, and the change had successfully gone out to our non-production environments more slowly than normal.

How We Perform Changes

Obviously there are exceptions to every rule, but mostly actions are taken via the use of Jenkins. A job is defined for many of the common actions we need to take; deploys are all scripted in this way for example. This allows us to perform actions on a large number of servers consistently. If there isn’t a specific job in Jenkins to perform an action, we have a job that allows us to run a command we define ourselves. When planning a change we write out the steps we will take, and provide evidence that these steps produced the desired result in our test environments. When choosing a Jenkins job to run we choose not only the appropriate job, but also any options we will pass to that job. That plan is then read by another Engineer, generally one of the Senior Engineers, and preferably one uninvolved in the change being planned. If the approving Engineer has any doubts then the change needs to be amended to address those doubts.

What Was the Plan

So, on to our change. The plan was reasonably straightforward.

- Deploy configuration changes to our production environment in Chef

- Run chef-client on all the Java application servers to make the configuration changes in a consistent manner

- Restart the Java applications in sequence to pick up those changes

It is worth explaining that last step in more detail, as that is where things did not go according to plan. As multiple different applications were being restarted the plan did not use the application restart job that we have scripted in Jenkins. This job is designed to restart a single application. Instead the job mentioned earlier to run commands we define was used. It was planned as:

- Environment: Production

- Search: All our Java Application Servers

- Command: Restart Java Application

- Concurrency: 1

These exact steps had worked in all our other environments without issue.

What Went Wrong?

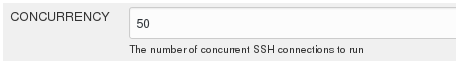

As we all know, mistakes happen, people are imperfect beings, and that’s why we script as much of our work as we can. In this case the Engineer forgot to set the Concurrency on the job to restart the applications. In the Application Restart job, this would have caused a problem, but not a major one, as it always starts with a single server, and prompts the Engineer to check that the application has started cleanly before moving on. But that job was not used; the job that was used was an older job, it had fewer safe guards, and unfortunately it had a default value for the concurrency.

As this job is used widely within the business, and may be used across hundreds of servers at a time it makes sense to have a high default concurrency, however in this instance that was sufficient to restart the application on all the Java application servers at once. These applications handle a number of functions surrounding customer logins, and consequently on 23 March at 10:27am all customer logins across all Sky Betting & Gaming products failed, for approximately one minute.

As this job is used widely within the business, and may be used across hundreds of servers at a time it makes sense to have a high default concurrency, however in this instance that was sufficient to restart the application on all the Java application servers at once. These applications handle a number of functions surrounding customer logins, and consequently on 23 March at 10:27am all customer logins across all Sky Betting & Gaming products failed, for approximately one minute.

What Went Well

We try to work with a no-blame culture. It isn’t the fault of the individual, it is the fault of the platforms and procedures that allowed a mistake to have an undesired impact. So when the Engineer performing this change immediately put their hand up and said “I have caused an outage” it allowed the on-call engineers, and other interested parties to get on with the task of fixing the problem, and investigating the impact, without having to look at why the incident happened.

It’s important not to panic when things go wrong. A natural instinct is to “Do Some Thing!” when things are going wrong, but the wrong thing done quickly can sometimes do more damage than doing nothing. Based on the Engineer’s account of what happened during this incident they saw the restart job connect to all the Java application servers at once, and nearly killed the job then and there. This would have stopped that job from bringing the applications back up, and would have not been good. Fortunately they paused, and thought about what they wanted to do, and didn’t take that action. This is always a useful way to handle the panic you will feel in that situation, pause and reflect on what you want to do, the extra time can bring clarity, it is that clarity that panic robs from us.

They asked for help. This is also important; we are a large organization, individual Engineers are not alone, and are not expected to know everything. The Engineer called for help, and some other Engineers who were more familiar with the application were able to confirm that they came back up cleanly, and also investigate the extent of the impact. Approximately 500 logins failed in that minute.

We have reviewed the incident after the fact, and the Engineer was open and honest about what they did. This has allowed us to improve our procedures, including adding extra scrutiny over the use of the Jenkins job that failed us in this instance. And further education on how to use the Application Restart job, that would actually have been able to do the job we needed, but the Engineer who planned the change was not familiar with it, as it is most often called as part of a deploy, and not directly.

What’s So Hard About That?

I started by saying that I wanted to tell you why mentoring is hard. So many people have told this Engineer that they did the right thing, that it’s not their fault, and that everyone makes mistakes. I know that this doesn’t make them feel good. I know that the impact this had on the business, on our customers, and on their colleagues fills them with guilt. And I know that whenever something like this happens, it is part of my job to help them pick themselves up and carry on. I can do my best to try and assuage that guilt, but I know it is always going to be there. I can only tell them it gets better.

I know they feel this guilt, because on this occasion it was my change, and it was my mistake. Which just goes to show that mistakes can happen no matter how experienced or senior you are, so as I tell the Engineers I work with, and as I try to tell myself, “Don’t be so hard on yourself, it could happen to anyone”.