Zero-Downtime Kubernetes Deployments

There has been a lot of work going on in Core Customer over the last few months to migrate our OIDC/OAuth2 identity service from our tactical container platform to on-premises Kubernetes clusters. I’ve spoken about our homebrew container platform (Corbenetes) before, but here’s the essentials.

We built a container platform using Chef and Docker as a stepping stone to Kubernetes. It utilised our existing apps-on-virtual-machines deployment and operational patterns, and so this allowed Software Engineers to develop their applications in a cloud-native manner in a familiar way, and without needing to use the (at the time) brand new Kubernetes platform.

Now we have a very high level of confidence in said new Kubernetes platform, we are migrating projects over and decommissioning our middle-ground solution.

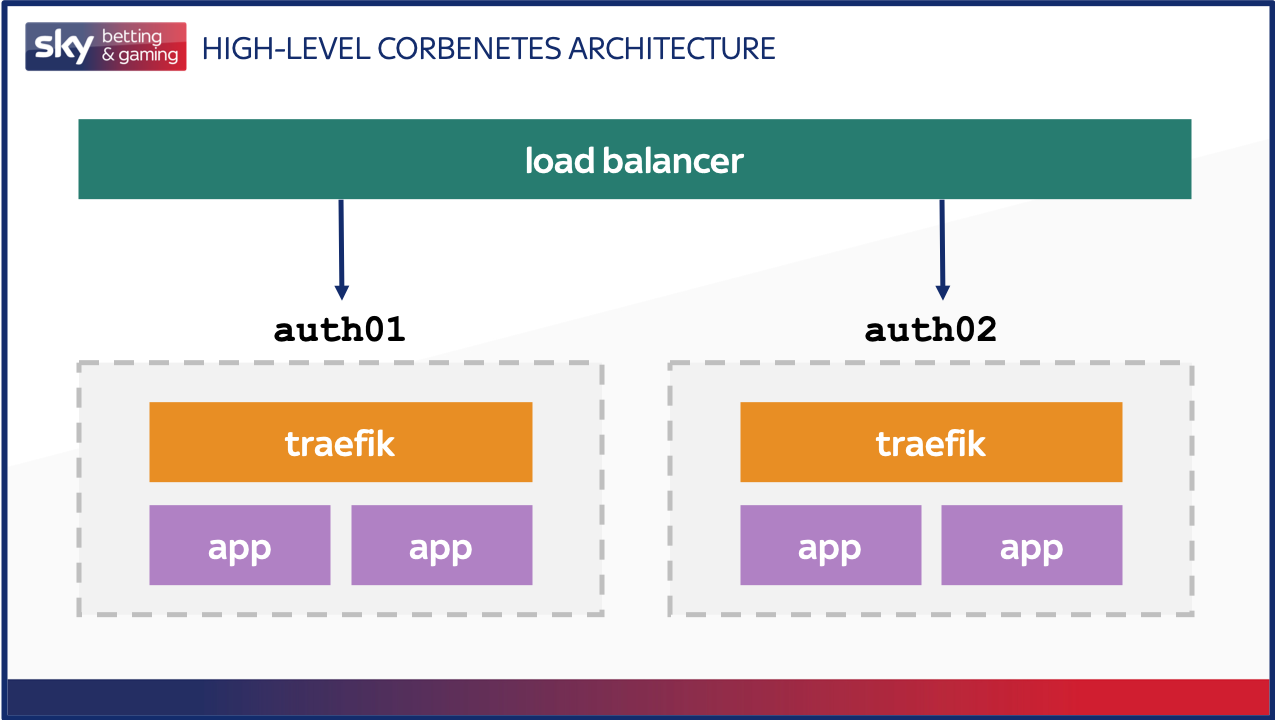

The migration actually went a lot smoother than we anticipated, especially seeing as this is the first large-scale service we have built on Kubernetes. One thing we hadn’t initially accounted for was the different ways in which health checks would be used by the underlying platform to detect whether or not traffic should be sent to a specific container. For some context, our current Corbenetes architecture looks similar to the below with one traefik container and two app containers per host (alongside a number of supporting containers for logging and metrics that aren’t shown here).

Traefik acts as a proxy, handling both TLS-termination and sending requests to the two backends that are available on the host. The upstream load balancer examines the health endpoints of the applications (via traefik) as well as traefik’s own /ping endpoint. When we do a restart of the application as part of a release, we stop traefik, which allows existing connections to the application to clear down, and takes it out of service in the load balancer so no further requests are sent to this host. Once the applications have finished dealing with their requests, they too are closed down. Because of this, the shutdown of the application itself doesn’t need to be the cleanest, as by the time it receives the shutdown signal there are no requests being served by it.

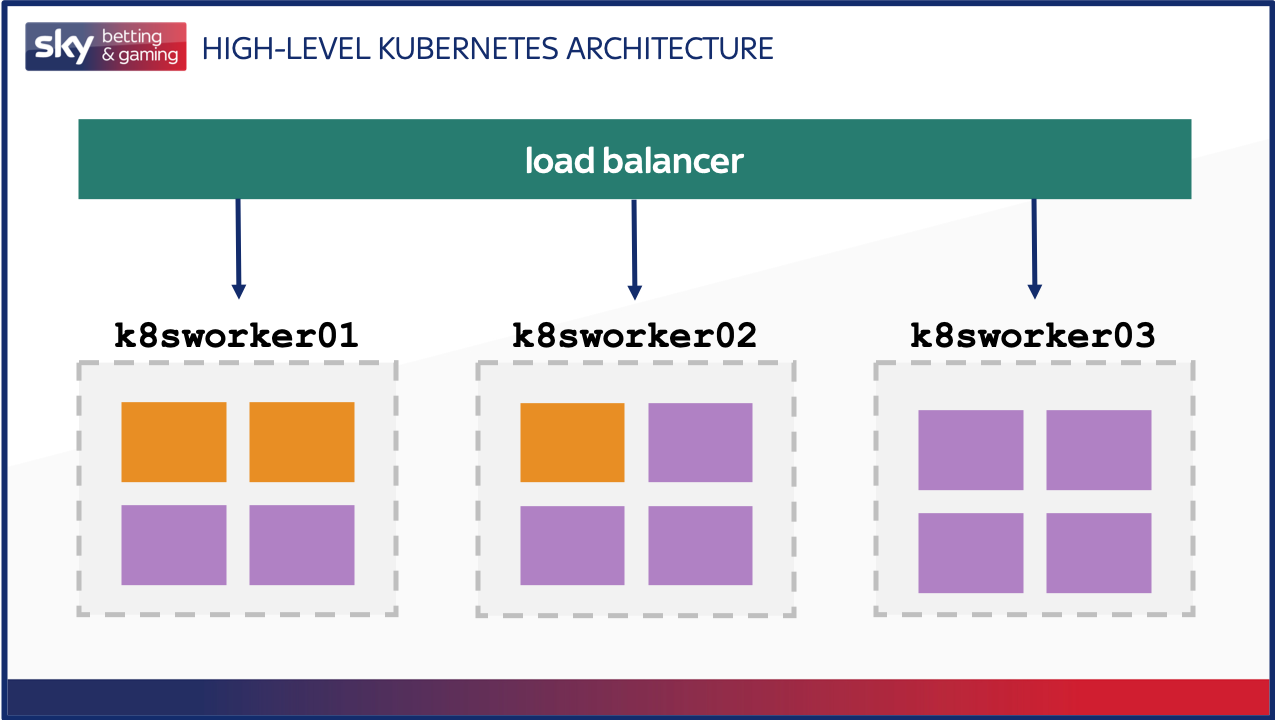

The following image shows our current architecture now we’re on Kuberbetes, again very high level. We have traefik and app Pods, each exposed with a Service (essentially a cluster of Pods and a policy allowing access to them). The traefik Service is exposed outside the cluster to allow incoming connections from the load balancer, and we make use of the Ingress resource to direct traffic destined for specific URLs to the app backend Service.

How Kubernetes handles health checks

Our health checks are defined as part of our Deployment manifest, for both traefik and the application. Initially we used the same health check endpoints as we had been using previously. Our manifest looked a little like this.

traefik

livenessProbe:

failureThreshold: 2

httpGet:

path: /ping

port: 80

scheme: HTTP

initialDelaySeconds: 10

periodSeconds: 5

readinessProbe:

failureThreshold: 2

httpGet:

path: /ping

port: 80

scheme: HTTP

periodSeconds: 5

application

livenessProbe:

failureThreshold: 2

httpGet:

path: /ping

port: 8081

scheme: HTTP

initialDelaySeconds: 10

periodSeconds: 5

readinessProbe:

failureThreshold: 2

httpGet:

path: /ping

port: 8081

scheme: HTTP

periodSeconds: 5

This seemed to work out alright. Our Pods were up and running when we expected them to be, and when we force stopped the application, the health check went bad and the Pod was deleted. It was at this point we started doing extensive performance testing of the application on this new platform. We noticed an issue with cold starts. It appeared that the first time a non-health check request was made to each application Pod, the response time was around six seconds. The was obviously a suboptimal situation, and another reason why we do lots of performance testing using production-like load profiles.

After this first slow response, the application was absolutely fine. Turns out that the application doesn’t compile its JavaScript components until the first page load.

It’s alive, but is it ready?

It’s almost as though the team that built Kubernetes knew this would be a thing, as they specifically define both a livenessProbe and a readinessProbe that can be applied to the Pods. Their own documentation explains the difference between the two:

- livenessProbe defines when to restart a container, e.g. the

/pingendpoint returns a bad response - readinessProbe defines when a container is ready to start accepting traffic, e.g. a script has run to synchronise data in your stateful application

In our case, we needed to change our readinessProbe to try and load the /login endpoint, and allow the application to be properly ready for accepting all traffic, not just health check traffic.

readinessProbe:

failureThreshold: 5

httpGet:

path: /login?client_id=auth_provider

port: 8081

initialDelaySeconds: 25

periodSeconds: 10

timeoutSeconds: 1

successThreshold: 1

This was a great success. Each Pod took about 15 seconds longer to start, but that’s a small price to pay to be confident in the ability of the Pod to handle traffic straight away. We went back to our performance testing and low and behold… we still saw issues with dropped requests during an application release, or scale down of the Pods.

Something about how this application works did not appreciate the way in which Kubernetes was terminating it.

Let me down gently

When Kubernetes decides that it needs to terminate a Pod (whether this be to evacuate a host, move things around for resource utilisation purposes, or just because there is change to the Deployment warranting the creation of new Pods) it sends a SIGTERM (graceful shutdown request) to PID 1 of the container and waits for up to thirty seconds. In our case, PID 1 was the node parent process.

Remember the way we used to stop the applications on Corbenetes? We’d cut them off from receiving new requests and then eventually stop the application itself. Because at a basic level there is no link in Kubernetes between the state of the application Pods, and the state of the traefik Pods, we can’t hide the application behind traefik any more.

Thankfully, we had a way around this. We could use the Kubernetes container hooks to implement a PreStop hook to do something before Kubernetes attempts to stop the container. We knew that straight killing the node parent was bad, even if it was graceful, so we experimented with the best way to gracefully terminate the container.

lifecycle:

preStop:

exec:

command: [

"sh", "-c", "sleep 2 && kill -15 $(pidof node | awk '{print $1}') && sleep 2"

]

We ended up with this PreStop hook, which waits a couple of seconds, then sends a SIGTERM to the node child process, before waiting for another couple of seconds.

We went back to our performance tests and it was smoother than the proverbial. No matter how aggressively we were terminating Pods and restarting Deployments (the quickest way to test a release without actually releasing), we saw absolutely no degradation in service whatsoever.

This was all fine and dandy, but it taught us an important lesson: even if you are moving from one container-based platform to another, there is no such thing as a lift-and-shift. Each of them have their own nuances that need to be addressed. Now we know that Kubernetes is our standard, and we know how to handle zero-downtime deployments for our applications, we can properly spec out work in future, and not spend days chasing our tail trying to work out why it doesn’t just work.